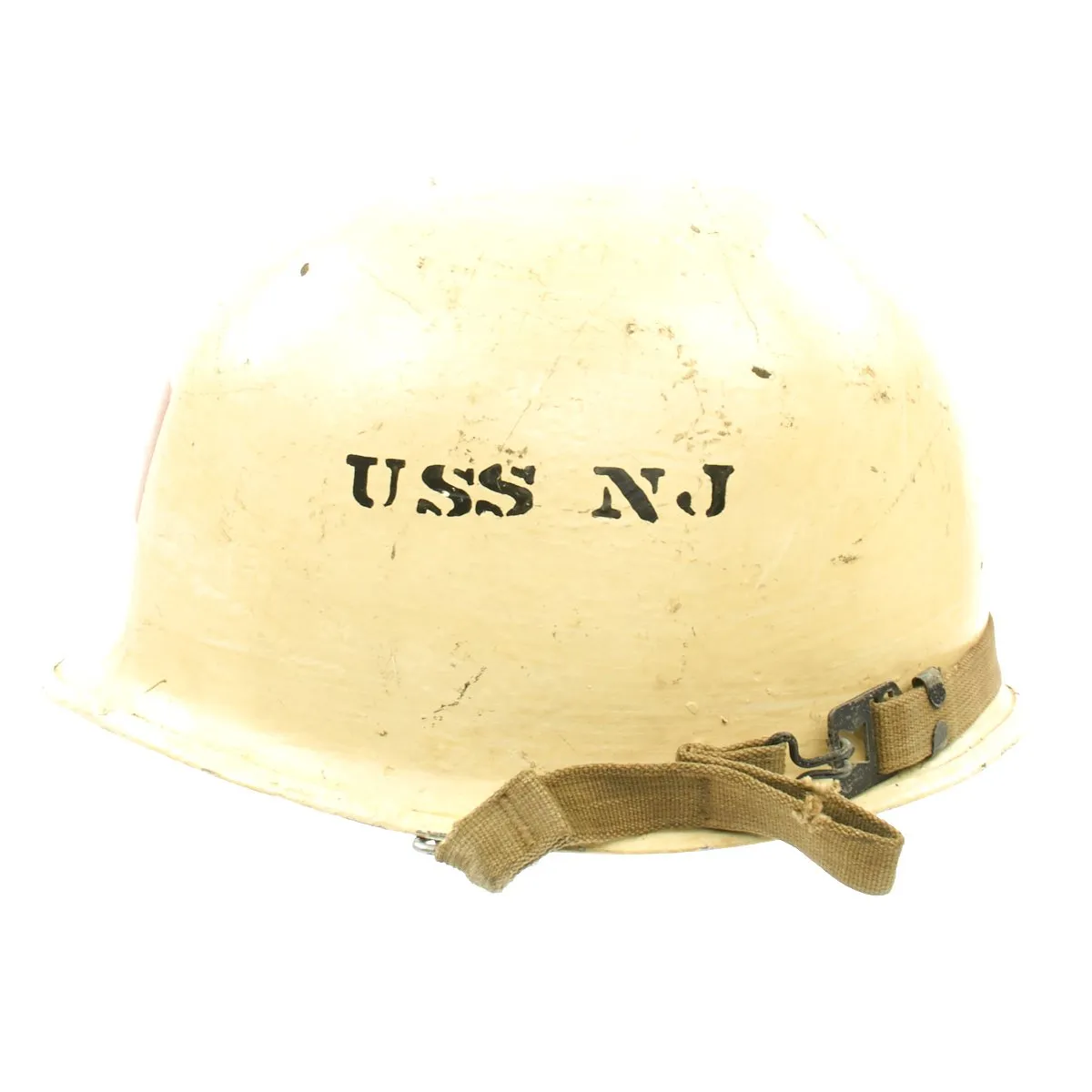

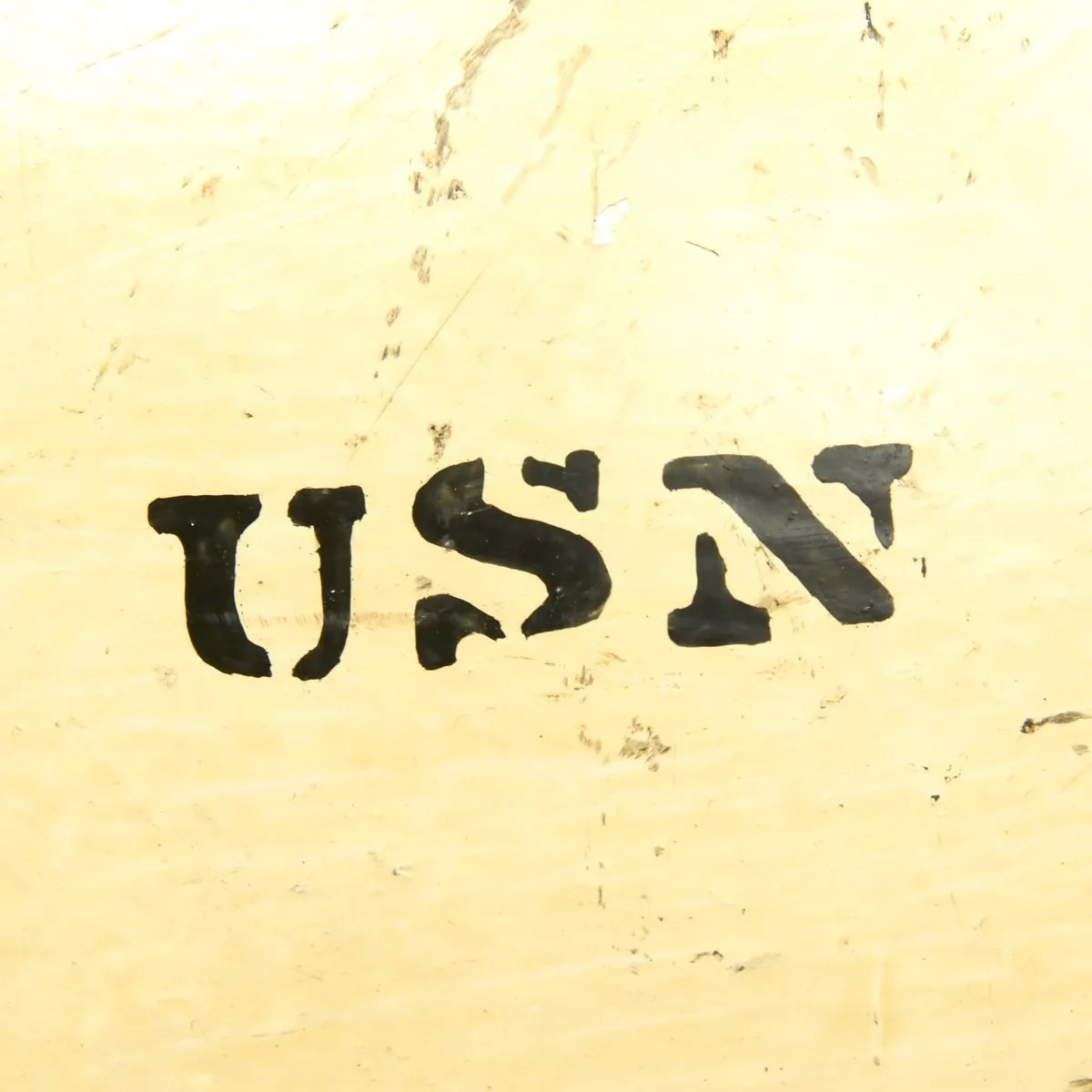

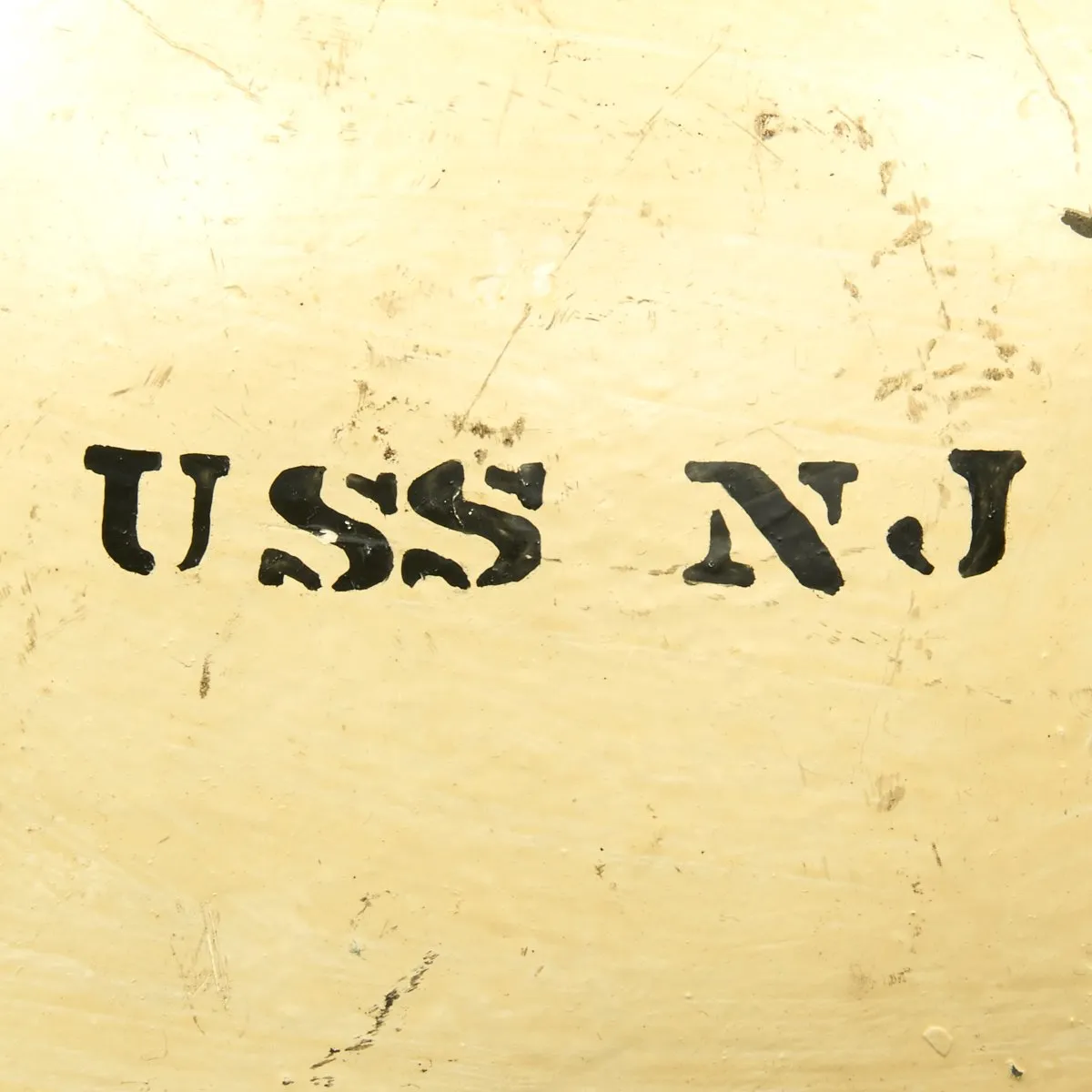

Original Item: One-of-a-Kind. This excellent genuine WWII U.S. Navy issue helmet issued to a Hospital corpsman (medic). This example in very good condition features a shell painted white with red cross to front USN on right side and USS NJ on left side. The shell is a front seam, swivel bale, M1 made by Schlueter. It features the original chinstrap. The liner is Firestone and has seen significant use, the HBT straps are a bit brittle and the sweatband and chinstrap are absent.

Shakedown and service with the 5th Fleet, Admiral Spruance

New Jersey completed fitting out and trained her initial crew in the Western Atlantic and Caribbean Sea. On 7 January 1944 she passed through the Panama Canal war-bound for Funafuti, Ellice Islands. She reported there 22 January for duty with the United States Fifth Fleet, and three days later rendezvoused with Task Group 58.2 for the assault on the Marshall Islands. New Jersey screened the aircraft carriers from Japanese attack as planes from Task Group 58.2 flew strikes against Kwajalein and Eniwetok 29 January – 2 February, softening up the latter for its invasion and supporting the troops who landed on 31 January.

New Jersey began her career as a flagship 4 February in Majuro Lagoon when Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commanding the 5th Fleet, broke his flag from her main. Her first action as a flagship was in Operation Hailstone, a two-day surface and air strike by her task force against the major Japanese fleet base on Truk in the Carolines. This attack was coordinated with the assault on Kwajalein, and effectively interdicted the Japanese naval retaliation to the conquest of the Marshalls. On 17 and 18 February, the task force accounted for two Japanese light cruisers, four destroyers, three auxiliary cruisers, two submarine tenders, two submarine chasers, an armed trawler, a plane ferry, and 23 other auxiliaries, not including small craft. New Jersey destroyed a trawler and, with other ships, sank the destroyer Maikaze. New Jersey also fired on an enemy aircraft that attacked her formation. The task force returned to the Marshalls 19 February.

Between 17 March and 10 April, New Jersey first sailed with Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher's flagship Lexington for an air and surface bombardment of Mille, then rejoined Task Group 58.2 for a strike against shipping in the Palaus, and bombarded Woleai. Upon his return to Majuro, Admiral Spruance transferred his flag to Indianapolis.

New Jersey's next war cruise, 13 April – 4 May 1944, began and ended at Majuro. She screened the carrier striking force which gave air support to the invasion of Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay and Humboldt Bay, New Guinea, 22 April, then shelled shipping and shore installations at Truk 29 April – 30 April. New Jersey and her formation shot down two enemy torpedo bombers at Truk. Her 16-inch salvos pounded Ponape 1 May, destroying fuel tanks, badly damaging the airfield, and demolishing a headquarters building.

After rehearsing in the Marshalls for the invasion of the Marianas, New Jersey put to sea 6 June in the screening and bombardment group of Admiral Mitscher's Task Force. On the second day of preinvasion air strikes, 12 June, New Jersey shot down an enemy torpedo bomber, and during the next two days her heavy guns battered Saipan and Tinian, in advance of the marine landings on 15 June.

The Japanese response to the Marianas operation was an order to its main surface fleet to attack and annihilate the American invasion force. Shadowing American submarines tracked the Japanese fleet into the Philippine Sea as Admiral Spruance joined his task force with Admiral Mitscher's to meet the enemy. New Jersey took station in the protective screen around the carriers on 19 June 1944 as American and Japanese pilots dueled in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. That day and the next would cripple Japanese naval aviation; in what would become known as the "Marianas Turkey Shoot", the Japanese lost some 400 planes for less than two dozen American aircraft in return. This loss of trained pilots and aircraft was equaled in disaster by the sinking of the Japanese aircraft carriers Taihō and Shōkaku by the submarines Albacore and Cavalla, respectively, and the loss of Hiyō to aircraft launched from the light aircraft carrier Belleau Wood. In addition to these losses, Allied forces succeeded in damaging two Japanese carriers and a battleship. The anti-aircraft fire of New Jersey and the other screening ships proved virtually impenetrable; two American ships were slightly damaged during the battle. Only 17 American planes were lost in combat.

New Jersey's final contribution to the conquest of the Marianas was in strikes on Guam and the Palaus from which she sailed for Pearl Harbor, arriving 9 August. Here she broke the flag of Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr.,[8] 24 August, becoming flagship of the United States Third Fleet. On 30 August New Jersey set sail from Pearl Harbor, and for the next eight months was based at Ulithi to lend support to Allied forces operating in the Philippines. In this span of the Pacific War, fast carrier task forces ranged the waters off the Philippines, Okinawa, and Formosa, making repeated strikes at airfields, shipping, shore bases, and invasion beaches.

In September the targets were in the Visayas and the southern Philippines, then Manila and Cavite, Panay, Negros, Leyte, and Cebu. Early in October raids to destroy enemy air power based on Okinawa and Formosa were begun in preparation for the Leyte landings of 20 October 1944.

This invasion brought on the last great sortie of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Its plan for the Battle of Leyte Gulf included a feint by a northern force of planeless heavy attack carriers to draw away the battleships, cruisers and fast carriers with which Admiral Halsey was protecting the landings. This was to allow the Japanese Center Force to enter the gulf through San Bernardino Strait. At the opening of the battle planes from the carriers guarded by New Jersey struck hard at both the Japanese Southern and Center Forces, sinking a battleship 23 October. The next day Halsey shaped his course north after the decoy force had been spotted. Planes from his carriers sank four of the Japanese carriers, as well as a destroyer and a cruiser, while New Jersey steamed south at flank speed to meet the newly developed threat of the Center force. It had been turned back in a stunning defeat when she arrived.

New Jersey rejoined her fast carriers near San Bernardino 27 October 1944 for strikes on central and southern Luzon. Two days later, the force came under suicide attack. In a melee of anti-aircraft fire from the ships and combat air patrol, New Jersey shot down a plane whose pilot maneuvered it into the port gun galleries of Intrepid, while machine gun fire from Intrepid wounded three of New Jersey's men. During a similar action 25 November three Japanese planes were shot down by the combined fire of the force, part of one flaming onto the flight deck of Hancock. Intrepid was again attacked; she shot down one would-be kamikaze aircraft, but was crashed by another despite hits scored on the attacker by New Jersey gunners. New Jersey shot down a plane diving on Cabot and hit another plane which smashed into Cabot's port bow.

On 18 December 1944 the ships of Task Force 38 unexpectedly found themselves in a fight for their lives when Typhoon Cobra overtook the force— seven fleet and six light carriers, eight battleships, 15 cruisers, and about 50 destroyers— during their attempt to refuel at sea. At the time the ships were operating about 300 miles (500 km) east of Luzon in the Philippine Sea.[9] The carriers had just completed three days of heavy raids against Japanese airfields, suppressing enemy aircraft during the American amphibious operations against Mindoro in the Philippines. The task force rendezvoused with Captain Jasper T. Acuff and his fueling group 17 December with the intention of refueling all ships in the task force and replacing lost aircraft.

Although the sea had been growing rougher all day, the nearby cyclonic disturbance gave relatively little warning of its approach. Each of the carriers in the Third Fleet had a weatherman aboard, and as the fleet flagship New Jersey had a highly experienced weatherman: Commander G. F. Kosco, a graduate of the aerology course at Massachusetts Institute of Technology who had also studied hurricanes in the West Indies; despite this, none of these individuals or staffs were able to give Third Fleet due warning of the impending typhoon.[10] On 18 December, the small but violent typhoon overtook the Task Force while many of the ships were attempting to refuel. Many of the ships were caught near the center of the storm and buffeted by extreme seas and hurricane-force winds. Three destroyers—Hull, Monaghan and Spence—capsized and sank with nearly all hands, while a cruiser, five aircraft carriers, and three destroyers suffered serious damage.[9] Approximately 790 officers and men were lost or killed, with another 80 injured. Fires occurred in three carriers when planes broke loose in their hangars, and some 146 planes on various ships were lost or damaged beyond economical repair by fires, impact damage, or by being swept overboard.[10] As with the other battleships of TF 38, skillful seamanship brought New Jersey through the storm largely unscathed. She returned to Ulithi on Christmas Eve to be met by Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz.

Located in the center of the U.S.S. New Jersey's bridge, the Conning Tower, AKA "battle conn", contained the equipment required to "conn" the ship. This includes a ship's wheel, the ship's revolutions per minute indicator, engine telegraphs, and communications gear. A mannequin is visible in this photo. A portion of a small viewing port is visible at the back of the space. The outer shell of the Conning Tower consists of 17 inches of solid steel armor, designed to resist the impact of a 1-ton shell. The door for this entrance (not shown) weighs more than a ton.

Service with Battleship Division Seven, Admiral Badger

New Jersey ranged far and wide from 30 December 1944 to 25 January 1945 on her last cruise as Admiral Halsey's flagship. She guarded the carriers in their strikes on Formosa, Okinawa, and Luzon, on the coast of Indo-China, Hong Kong, Swatow and Amoy, and again on Formosa and Okinawa. At Ulithi 27 January Admiral Halsey lowered his flag in New Jersey, but it was replaced two days later by that of Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger II commanding Battleship Division 7.

In support of the assault on Iwo Jima, New Jersey screened the Essex group in air attacks on the island 19 February – 21 February, and gave the same crucial service for the first major carrier raid on Tokyo 25 February, a raid aimed specifically at aircraft production. During the next two days, Okinawa was attacked from the air by the same striking force.

New Jersey was directly engaged in the conquest of Okinawa from 14 March until 16 April. As the carriers prepared for the invasion with strikes there and on Honshū, New Jersey fought off air raids, used her seaplanes to rescue downed pilots, defended the carriers from suicide planes, shooting down at least three and assisting in the destruction of others. On 24 March 1945 she again carried out the role of heavy bombardment, preparing the invasion beaches for the assault a week later.

During the final months of the war, New Jersey was overhauled at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, from which she sailed 4 July for San Pedro, Pearl Harbor, and Eniwetok bound for Guam. Here on 14 August she once again became flagship of the 5th Fleet under Admiral Spruance. Brief stays at Manila and Okinawa preceded her arrival in Tokyo Bay 17 September, where she served as flagship for the successive commanders of Naval Forces in Japanese waters until relieved 28 January 1946 by Iowa (BB-61). As part of the ongoing Operation Magic Carpet New Jersey took aboard nearly a thousand homeward-bound troops with whom she arrived at San Francisco 10 February.

In World War II the production of the M1 helmet began in June 1941 and ceased in September 1945. The total production of M-1 helmet shells during the war reached 22,000,000. Of these about 20,000,000 were produced by the main contractor McCord Radiator and Manufacturing Company of Detroit. Although McCord was supposed to be the single source of M-1 helmet shells, by the summer of 1942 a second company was enlisted to help the production effort. This was Schlueter Manufacturing of St. Louis, Missouri.

Schlueter began production of its M-1 helmet shells in January 1943. Schlueter produced only 2,000,000 M-1 helmet shells during the war (both fixed and swivel). They placed an S stamp on their helmet shells above their "heat temperature stamp.

Aside from the markings, there are some subtle differences between a McCord and Schlueter M-1 helmet shell. This can be found on the rims. A Schlueter helmet shell has a much straighter profile than the classic McCord brim. Also, the spot welds used to attach the chin strap bales and secure the stainless steel rim are larger and oval shaped on Schlueter helmets than on McCord.

This Schlueter helmet is a very nice example and still retains original parts and paint. The steel shell is stamped with a large S indicating Schlueter manufacture and dating from 1944. M-1 helmet shell has an stainless steel rim with seam in the front. Stainless steel rims were both rust resistant and had "non-magnetic qualities" that reduced the chance of error readings when placed around certain sensitive equipment (such as a compass). This helmet features late war rear seam rim and late war production swivel bales. The shell chin strap is original.

This true US WWII M-1 helmet liner be identified through the frontal eyelet hole. Other correct WW2 features include cotton herringbone twill (HBT) cloth suspension. This HBT suspension is held tightly within the M-1 helmet liner by rivets and a series of triangular "A" washers. The three upper suspension bands are joined together with a shoestring. This way the wearer could adjust the fit.

Schlueter helmets have become extremely difficult to find in recent years, especially genuine named fixed bale versions. Almost certainly to appreciate in value year after year.

WW2 Medic helmets are among the most sought after of all M1 helmets and have become very difficult to find in recent years, especially genuine WW2 issue liners with the correct HBT straps. Almost certainly to appreciate in value year after year!